WelCom May 2022

The big picture, and the bigger picture

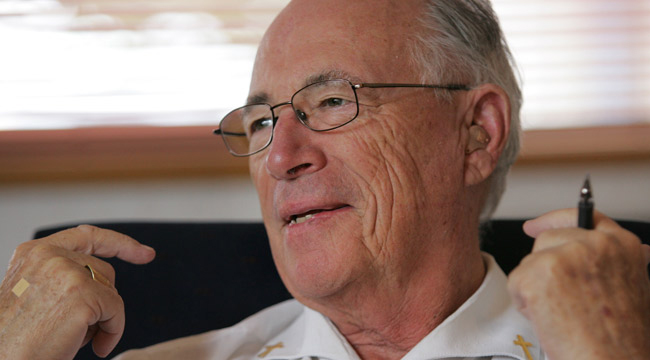

Emeritus Bishop Peter Cullinane of the Diocese of Palmerston North invites young people to consider the future with wonder and unending awe, being true to our authentic human nature and loving others the way God loves us.

Dear young people – it is especially you I am thinking of as I allow these thoughts to unravel. You will be architects of the future. Amazing science and technology will open doors we haven’t even come to yet. Hopefully, you will always be guided by what it means to be authentically human, which involves more than what science and technology can tell us. In fact, it also helps us to safeguard against the abuse of science and technology.

You might glean from these ponderings that I am a fan of Professor Brian Cox. As a former musician with the British bands D:Ream and Dare, and associate of Monty Python’s comedy troupe, Cox presumably believes life is to be enjoyed. He is right. As professor of particle physics in the School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Manchester, and BBC documentary presenter, he clearly finds the universe cause for great wonder.

It’s interesting that science and faith both evoke a sense of wonder and awe. Science is in wonder at what exists, from its smallest details to its greatest dimensions. No matter how far back scientists look for the universe’s origins, science can only wonder at what exists. Faith is in wonder that anything exists at all, because God didn’t need to create. We need to find ourselves in wonder at what it means to be part of something that might not have existed. ‘The world will never starve from want of wonders; it will starve from want of wonder.’ (GK Chesterton.)

“The world will never starve from want of wonders; but only for want of wonder.” – GK Chesterton.

I find myself both enchanted and challenged by the history of the universe – 13.8 billion years to the first stars; now billions of stars within each galaxy, and trillions of galaxies, and planets formed by the stars; our planet formed from colliding debris over 4.5 billion years, at just the right distance from the sun for life to develop; distances measured in billions of light years; gravitational forces that could kick planets into different trajectories; the combination of variables that gave us the world that is, instead of all the others that could have been but never will be…! And planet Earth is microscopic within our solar system, let alone within the wider universe of other galaxies.

But it is also special. The massive transformations that were part of its geo-history led to further transformations in the development of life in its marvellous and complex forms (bio-history). Last of all, and very late, human life emerged, and what emerges from human freedom – human history. Each of those histories, reason for unending awe.

Eventually, out of what had been a vast wasteland of rock, volcanoes, lava, gases and acidic seas, someone called Beethoven surfaced, who could pull together the sounds that make a symphony. At the right time, unlikely raw materials had been transformed into a variety of instruments and delicate sounds that would beautifully blend and move together – moving us and drawing us together. That’s a long way from when the first boulders bashed against each other to form a planet capable of this – and every other wonder like it.

But if the past is mind-boggling, it’s the future that really challenges me. Our planet, scientists say, is destined to end up like the other planets – burned out and dead! Some scientists surmise that by the time planet Earth dies we will have established ourselves on some other planet(s). Who knows? What we do know is that any planet that might have lit up to become our new home had better not count on getting its heat from the sun; it will have been the sun’s demise that ensures Earth’s demise. Cruising around from one dying planet to another seems a lot of trouble to go to for unpromising returns.

Brian Cox relishes life; he says life is what gives the universe its meaning. With sincerity and courage, he asks all the hard questions. Following the evidence of the sciences, he tells us that in some trillions of years all the other suns will have burned out like our own, and ‘all life and all meaning’ will vanish with them. Where there was void before our universe came into existence, there will be void again. I suggest the question of meaning cannot so easily be put aside. Even if, as some surmise, our universe originated from some previous universe that also came and went, and so on over and over, the question always remains: why is there not just nothing at all?

Of course, time is on humanity’s side: the sun is good for another five billion years. But however long or short the timeframe, it matters now because it is our present lives that are either pointless already if they are pointless in the end; or wonderful already if they are on their way to a wonderful future.

The overall direction of evolution has been towards life, with its potential for more wonderful and complex transformations. Can evolution deliver what it seems to promise? Or is it just part of the planet’s life and destined to share its fate?

There was one transformation within the life of the planet that was qualitatively different from all others. It reached right into the life of the planet, but took that life beyond anything evolution could do. The Incarnation is about God’s personal participation in the life of the planet and in human history – surpassing all other reasons for wonder, joy and thanksgiving! A creation in which God has a stake is a creation with a future!! Jesus’ life – bringing healing, hope, peace, forgiveness and compassion into people’s lives ratified human nature’s deep hunch that this is what we were made for. And his resurrection confirmed that death does not have the last word.

Those who were witnesses to these things summed them up in their message that all creation is being ‘made new’ – with a newness that creation cannot bring about for itself. There is much at stake on this claim, because it means our lives will matter forever. The whole of life is different – already – when we know that:

- all the good fruits of human nature, and all the good fruits of human enterprise, we shall find again, cleansed and transfigured. (Second Vatican Council, Church in the World, n.39)

People we love, times that were special, good things we have done, all somehow belong with us in our future. What is truly precious to us now is never really lost. The sacrifices we make for what is good and right and just, do count. The planet Brian Cox has good reason to love, we have even greater reason to love.

So, how does this picture of our future sit with science’s claim that our planet will die? Some believe our spirits go off to Heaven, leaving material creation behind. That view originates from ancient pagan belief that material things are somehow bad and ultimately don’t belong. Christian belief is different, based on the ancient Hebrew belief that God made the whole of creation ‘good’, and human life ‘very good’. Our bodies are part of what it means to be human. It is our human nature, and the whole of creation, that is being ‘made new’.

“Jesus’ life – bringing healing, hope, peace, forgiveness and compassion into people’s lives ratified human nature’s deep hunch that this is what we were made for. And his resurrection confirmed that death does not have the last word.”

The early Christians spoke of the risen Christ as the ‘first fruits’ of this new creation. They emphasised that his resurrection involved his whole human nature. It was bodily, but was not a return to this life. It belongs to creation ‘made new’. In this new form they experienced his real presence among them. Reflecting on their experience, they now realised it was to be expected: ‘In a little while the world will no longer see me; but you will see me, because I live on, and you too will live’ (John 14:19).

God’s plan for our future does not discard material creation. It is the present form of material creation that will pass. It will be transformed in the way that Jesus was transformed through his death and resurrection. We don’t have language for that, because language is based on our experience of the world in its present form.

It hardly matters that the planet in its present form will die. What matters is that the Incarnation brought about a transformation that continues. What that leads to is what we call Heaven. There is more to the Incarnation than Santa Claus at Christmas and chocolate bunnies at Easter.

I indicated at the outset that our participation in the life of the planet and human history needs to be guided by what it means to be authentically human. Much hangs on this, including how we use the sciences and technology. So, what does ‘authentic’ mean in this context?

In the second century, St Iraneus said we are never more fully alive and true to our own nature than when we ‘see God’. Pausing to know we are in God’s presence sharpens our realisation that God never owed us our existence, or needed to create; we are part of what might never have been. That’s marvellous: it means that God, who didn’t need us, wanted us! When we know that, we become more alive.

That also means our existence is pure gift; so, we are true to ourselves most of all when we are being given, that is being there for others – in all the ways required by right relationships, with each other and with all creation. That is being true to our human nature – ‘authentic’.

It involves loving others the way God loves us: love that isn’t owed or measured or needing to be deserved is a circuit breaker – the kind of love that changes everything, and the only kind that can! Many Religious Orders, and lay movements based on the gospel, were founded to put that kind of loving into action. Outside the Catholic tradition it is exemplified in those religious movements which were based on the twin focus of social activism and a spiritual basis – for example, Methodism, Quakerism, and many others. Catholic social teachings about the dignity of every person and the sacredness of every life; the common good, including our common home; solidarity and option for the poor, are all premised on it. It’s hardly surprising Pope St John Paul II insisted that ‘humanity is the route the Church must take’.

Being true to our nature – ‘authentic’ – is compromised wherever a narrow focus on our own rights blinds us to our responsibility to be there ‘for others’; wherever deeper moments for noticing God’s presence are crowded out by noise, hurry, and the pressures of modern living; where the fast flow of information displaces understanding and wisdom; wherever superficiality replaces depth – for example, where even news programmes are presented through the prism of entertainment, sometimes even called ‘shows’….

Authenticity involves being counter-cultural. Knowing this, Pope St John Paul II told the New Zealand bishops to ‘make a systematic effort in your dioceses and parishes to open new doors to the experience of Christian prayer and contemplation’ (New Zealand bishops’ Ad Limina visit to Rome 1998). Contemplation means ‘seeing God’, noticing God’s presence, in the midst of life. This changes how we think and act. That is what the gospel means by ‘repentance’ and conversion. It’s about how we participate in creation’s newness, and its future.

The post Come, dream with me a dream that is coming true first appeared on Archdiocese of Wellington.

Palmerston North to Host Jubilee Youth Festival in August

Young Catholics

Published on 14th Jul, 2025

The day-long festival will take place on Sat 2 August in Palmerston North [..]

Life Teen Aotearoa Leadership Convention

Young Catholics

Published on 5th Oct, 2024

‘Sanctuary’ was the theme for the 2024 the Life Teen Aotearoa Leadership Convention in August [..]

NZCBC National Council for Young People meet in Wellington

Young Catholics

Published on 31st Aug, 2024

The council's role is to advise and advocate on behalf of young Catholics in NZ [..]

Action is the antidote for eco-anxiety

Young Catholics

Published on 31st Aug, 2024

Climate change – two words – is something we all dread to think about [..]

Registrations open for the Life Teen Leadership Convention

Young Catholics

Published on 2nd Aug, 2024

Wellington Archdiocese is hosting the Leadership Convention for youth ministers, 30 Aug - 1 Sept [..]