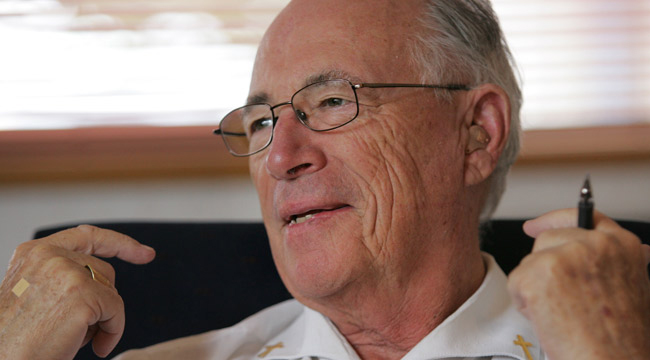

A continuing apostolate: Bishop Peter Cullinane

Published on 7th Jun, 2020

April this year marked 40 years since Peter Cullinane was ordained the first Bishop of the Palmerston North diocese. An outstanding pastoral leader, thinker and writer, he has been widely recognised over the years for his leadership and service to Church and community.

It is easy to underestimate the extent to which the Church has changed, says Bishop Peter Cullinane, reflecting on his life as a Catholic and 40 years as a bishop.

‘For those who can make the comparison, it is most obvious in the liturgy. When I was growing up, it really was ‘Father’s Mass‘, which everyone else only ‘attended.’ The call to holiness was more for clergy and Religious, and responsibility for the mission of the Church was for the bishops, and for laity who were ‘delegated’.

‘The move away from these symptoms of clericalism means accepting that the call to holiness is for all the baptised, and responsibility for the Church’s mission is also for all. That is a huge shift.’

Bishop Peter was ordained a priest for the Wellington Archdiocese in 1961. After parish ministry in Wellington during the 1960s, he was appointed to the Pastoral Centre in Palmerston North in the 1970s.

‘Working at the Pastoral Centre put me in touch with people from all over New Zealand who wanted the renewal introduced by the Second Vatican Council. We provided a wide range of courses – scripture, liturgy, catechetics, social justice – for laity, Religious and priests. The enthusiasm of people committed to renewal, and the heartbreaks of those who experienced opposition to it, highlighted for me the need for on-going adult formation at all levels. This became a priority in my ministry when I was made a bishop.’

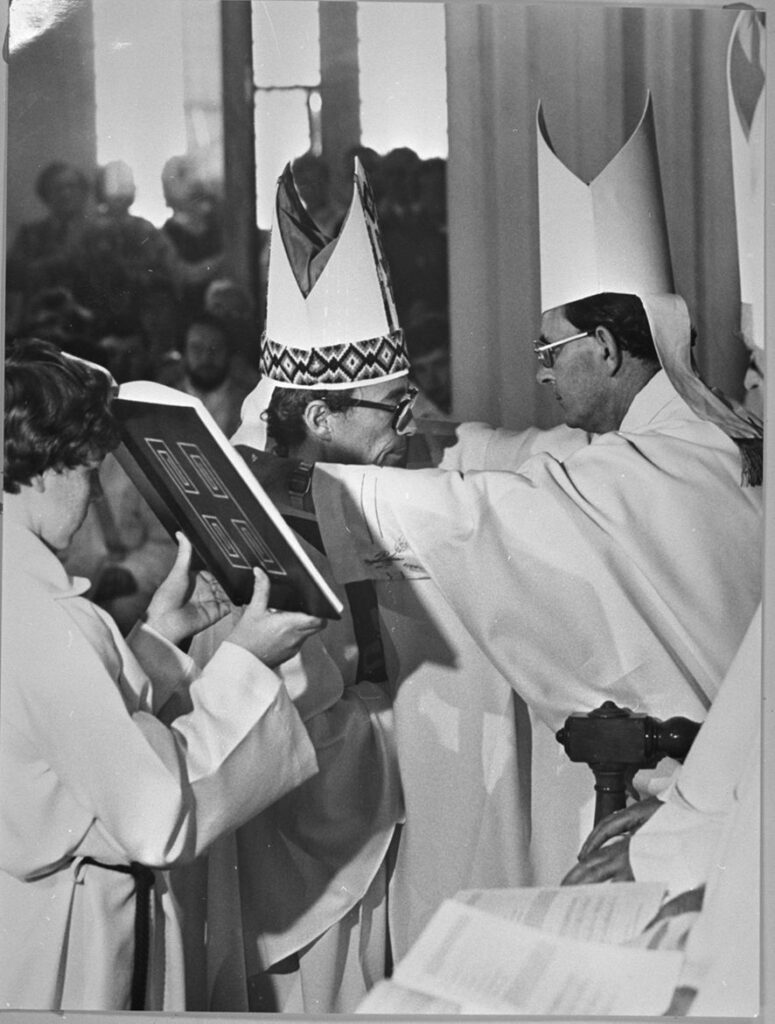

In 1980 the Archdiocese was divided up and the Palmerston North diocese was established, with Bishop Peter as its founding bishop.

‘My first office was a small kitchenette at the Pastoral Centre, which is a way of saying that administratively we started with nothing. The process of ‘disengagement’ between the Archdiocese and the Palmerston North Diocese, and the equitable sharing of assets, was carefully worked through by competent people from both dioceses, and the very fair-minded contribution of Cardinal Tom Williams.

‘But the main assets of the new diocese were its people, Religious and priests. Programmes of formation for lay ministries (Hands On and Waka Aroha) were important developments. So too was the appointment of lay women and men to important diocesan leadership positions, including Finance and Catholic education. Eventually we appointed Lay Pastoral Coordinators to lead parishes rather than amalgamate them.’

Other structural innovations were also introduced.

‘We felt able after a short time to “park” our Diocesan Pastoral Council in favour of five deanery pastoral councils, which were open to the participation of a much wider representation of the people of the diocese. We were not used to working together on this scale but it seemed consistent with the reason for creating the diocese in the first place: to bring people, priests and bishop into closer, more frequent, contact. It was that way of working together that Pope Francis is encouraging – a synodal journeying together, listening at grassroots, and sharing responsibility. The only way to get used to it was to do it.’

A bigger challenge was to enable the full participation of Catholic Māori, recalls Bishop Peter. The traditional model was that of the ‘Māori Mission’ which ran in parallel to parish life by Religious Orders.

‘The Māori Mission gave Māori a strong sense of belonging in the Church, and we are permanently indebted to the priests, Sisters and Brothers who made this possible. But there were weaknesses: it was dependent on Religious Orders, who were gradually less able to provide personnel. Further, so long as Religious were doing this work, parishes felt no need to become bi-cultural. Māori did not feel ‘at home’ in parish liturgies, programmes and apostolates.

‘The challenge was to help Māori feel that their place in the Church was not on the margins, while ensuring they could continue to experience their own ways of gathering. To help with this challenge, we established a Māori Apostolate Coordinating Board, with wide-open representation. The appointment of Koro Danny Karatea-Goddard as my vicar for Māori in 2007 was a milestone. So too was the ordination of three Māori priests, each on his own home marae: Steve Hancy in1988, and two widowers, Pehi Waretine in 1992, and Tamati Manaena in 1998.’

Catholic Education was a major challenge for the new diocese. Integration brought a huge financial burden as Catholic schools had to be brought up to the material standard of State schools.

‘The cost of doing this was beyond our means, and we were faced with having to decide which schools to keep and which to close, if we could not integrate them all. The government saved the day when it offered suspensory loans. There was no let-out earlier, however, when in the very first days of the diocese, I was told by the then Chancellor of the Archdiocese that I would need to halt a collection already in progress in Hawke’s Bay for the building of a new co-ed school, or face long-term, crippling indebtedness. It was a very upsetting time for us all.’

For many years Bishop Peter served on the International Commission for English in the Liturgy and has always shown a deep interest in liturgy and liturgical reform. Liturgical change, he says, brings challenges as well as great rewards.

‘Good liturgy takes us into the mystery of God’s presence, becoming an experience of awe, adoration, thanksgiving, deep joy…. But it is the awe and adoration of a community acting as one. This is what determines the meaning of participation and of reverence. Liturgy is not an individualistic, silo-type experience. Contrary to claims made in support of the 1962 Missal, the difference is not merely a matter of different liturgical tastes, because in practice, most of those who cling to the liturgy of their childhood are also absent from other aspects of parish life, ministries, apostolates and on-going formation. It is a partial way of dropping out.’

Asked to name some highlights, Bishop Peter cites the consecration of the diocese to the Holy Spirit as a milestone.

‘I was at a bishops’ meeting overseas on the Sunday we were to pray the prayer of consecration, and I remember getting up in the night to pray it at the same time as Sunday Masses in the diocese. We hope to renew this consecration on Pentecost Sunday this year.’

Another highlight was the appointment of a lay manager of the diocese, in lieu of the traditional ordained ‘chancellor’ with lay advisers.

‘The appointment of Owen Dolan as coadjutor bishop was a great milestone because we complemented each other in important ways. It turned out that on the Myers-Briggs Personality Type Indicator, one of us is INTJ and the other ENSP (guess which!) On hearing this, one of our priests commented that ‘now we have one whole bishop!’.

‘Another highlight was the renovation and re-dedication of our cathedral in 1988. The architect, Brian Elliot, was awarded for this work, and the cathedral was later featured on a New Zealand postage stamp. More importantly, while preserving its original gothic lines, it is now formatted for the renewed liturgy and it also features a number of Māori artifacts.’

And what has been the hardest thing about being a bishop?

‘In the early years of the diocese, perhaps it was matching the needs of priests with the needs of the people. Priests were truly prophetic in their witness to faithfulness, by being at their posts week in, week out, year in, year out. But pre-Vatican II seminary formation had not prepared any of us – priests, laity, bishops – for the challenges of the Council, including that understanding of the faith which leads to the greater involvement of laity, liturgical renewal, ecumenism, inter-faith relationships etc. And, nor had it prepared us for some of the problems that have occurred more recently. In many ways we have all been in a catching-up situation.’

Bishop Peter retired in 2012 though he has continued to keep himself busy, with his many writings appreciated by a large audience.

‘In a letter recognising my 32 years of leading the diocese, the Cardinal Prefect of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples spoke of a continuing apostolate of prayer and sacrifice. I really do find this is how I can continue to contribute. I am also very happy to be involved in parish ministry where and when required; at times more re-cycled than retired. The title ‘emeritus’ looks a bit prestigious and flattering, but my Latin dictionary brings it down to earth: ‘a veteran, old, disused…’. I’m loving the slower pace. And I do not regret my calling.’

Bishop

Published on 3rd Feb, 2026

[..]

Reflections on Renewal and the Year Ahead

Bishop

Published on 3rd Feb, 2026

Bishop John shares some reflections for the new year, and looks back over the 2025 Year of Jubilee [..]

Bishop John's 2025 Christmas Message

Bishop

Published on 18th Dec, 2025

'The dawn from on high shall break upon us' - Luke 1:78 [..]

Reflections From Two Years On

Bishop

Published on 1st Oct, 2025

I write this update for you on the day of my second anniversary of my ordination as the third Bishop [..]

Bishops Issue Letter on Occasion of Royal Commission Apology

Bishop

Published on 20th Nov, 2024

Earlier this week, we bishops gathered together and listened as the Prime Minister apologised to [..]